A Tangled Tale Untangled

This talk was given by by Mark Richards, former Chairman of the London based Lewis Carroll Society, at the May 2019 meeting of the Daresbury Lewis Carroll Society.

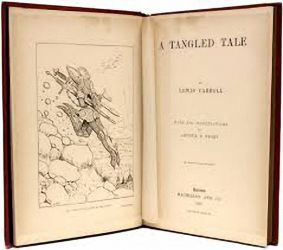

Mark treated us to an excellent talk on a not so well known book by Lewis Carroll - A Tangled Tale. There was a large amount of information in Mark’s talk which could easily fill several editions of this magazine so, with apologies to Mark, we have picked a few salient points to hopefully give you an interest in reading the book if you weren’t at the talk. Mark’s argument is that A Tangled Tale is the quintessential Lewis Carroll work – the one which best represents Carroll’s style of writing, his wit and his diverse interests.

First of all the book - It consists of ten chapters each called a Knot which presents a puzzle to the reader. At face value therefore the book is just a collection of puzzles which could be read and treated on their own. Each puzzle is presented as a story using carefully crafted text which is full of humour, word plays and some very unusual ideas.

For each Knot there are answers, but these are the least important. The solutions, how people derived their answers and Carroll’s response to them are the core of the book.

How The Tales Came About

The work started out as a series of short pieces written for a journal called The Monthly Packet a journal of light but educational pieces. One regular section of the Monthly Packet was called Spider Subjects – in which questions were set for the readers to investigate and send in their answers – the most appropriate answers being printed in a subsequent issue. Those sending in their answers were called spiders – and they generally sent in their work under pseudonyms, many of which had a touch of humour about them.

The first Knot came out in June 1880. The tale is of two knights returning to their hostelry having ascended and descended a small mountain. They converse in an ancient tongue discussing how long they have travelled and at what pace – one Knight in effect setting the other an arithmetical problem.

Subsequently not only a full solution to the problem was published, but also a detailed account of the answers. Like all good mathematics teachers, Carroll insisted on receiving the competitors’ workings not just the answer. Then using a very distinctive, humorous, but slightly mocking tone the mistakes were analysed and corrected. Finally the correspondents were placed in a Class list based on the quality of their work, with very few ever getting a First.

For example, at the end of the solutions to Knot 3 he says “A remonstrance has reached me from SCRUTATOR, ( one of the contributors’ pseudonyms) on the subject of Knot 1, which he declares was `no problem at all'. `Two questions,' he says, `are put. To solve one there is no data: the other answers itself.' As to the first point, SCRUTATOR is mistaken; there are (not `is') data sufficient to answer the question. As to the other, it is interesting to know that the question `answers itself', and I am sure it does the question great credit: still I fear I cannot enter it on the list of winners.”

This kind of joking with those sending in the answers is perhaps one of the most entertaining parts of the work. Sometimes he could be quite blunt when commenting on the correspondents’ answers . For example:

“Twenty-nine answers have been received, of which five are right, and twenty four wrong. These hapless ones have all (with three exceptions) fallen into the same error. Of the Twenty-four malefactors, one gives no working and so has no real claim to be named.”

Then each of the other twenty-three get it pretty well spelt out – they are called desperate wrong-doers or, they have the finger of scorn pointed at them.

Elsewhere the pseudonyms are thrown back at them as criticism – The one called An Ancient Fish, for example, is accused of having very ancient and fishlike ideas. In response to one called Tympanum he says “my Tympa is exhausted, my brain is numb.” And one called YY is accused of being two Y’s.

When Carroll first constructed the puzzle in Knot I and sent it for publication, he did not intend all the knots to be connected.

So it appears that the original idea was to produce a series of separate puzzles – not called “A Tangled Tale” but titled “Romantic Problems”. Some time after the first one had been written and perhaps

even published, he decided to connect the stories together so future Knots had the same cast of characters.

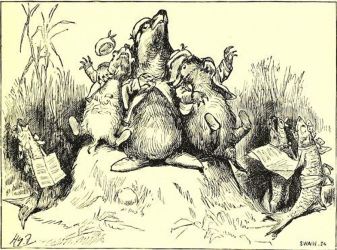

An interesting aside is the quotation beneath the heading for the final Knot is: “Yea, buns, and buns, and buns!” and is credited as an OLD SONG. It is actually the last line of the third verse of Carroll’s own poem about the Three Badgers from the yet to be published Sylvie and Bruno. Calling it an OLD SONG is a rather subtle Carrollian joke.

A Tangled Tale Emerges

It was now November 1884. It had taken four and a half years to get to the last Knot.

In a letter to McMillan in 1885 he asks them if they will publish the stories and says that he has six illustrations done by Mr Frost. Frost had previously produced sixty-five illustrations for Carroll’s Rhyme and Reason – demonstrating technical ability and a remarkable comic touch. Carroll obviously wanted ten illustrations – one for each Knot. It appears that he got ten, but four were not up to standard. Frost refused to re-draw them and so Carroll went ahead and published with just six.

All the Knots are included and so are all the solutions, comments and Class lists. Only a very few sentences were excluded. We get all the knots first, followed by all the other material and at the beginning of the answers we get the inevitable quotation: “A Knot said Alice – Oh do let me help to undo it!”

What is really surprising is how little attention the biographers give to the work:-

Anne Clark, in her biography, includes the book only with reference Carroll’s difficulties with his illustrator.

Cohen devotes just two paragraphs to it in a book of nearly 600 pages treating it only as a puzzle-book.

It seems that those who have read the stories have not bothered with the answers and critiques – which is where we can find the best pieces and possibly some insights into Carroll’s personality.

The Book As Literature

The book was probably an important experiment for Carroll and much of the Tale makes good reading. The framework seems to give Carroll the chance to write well, and somehow keeps him in check. There is a belief that Carroll was a much better writer when he had some self imposed constraints or what you might call a form of discipline. Looking-Glass in particular is a good example of this, where the theme of a chess-game was certainly a restriction on Carroll’s writing, but equally it gave him opportunities. Similarly, many of his acrostics are amongst his finest poetry.

A Tangled Tale fits in with this view. The need to talk directly to his readers was an opportunity, but the fact his remarks had to be responses to their comments stopped him from digressing too far or even sermonising. Compare this with Sylvie and Bruno, where he chose to make the framework fit the writing - rather than the other way round - in order that he could include anything he wanted and the book is a weaker because of it.

A Tangled Tale as the Quintessential Lewis Carroll Work

We first have to accept that Wonderland and Looking-Glass are really not typical Lewis Carroll works. We underestimate their sheer brilliance if we regard them as typical, they are in a league of their own and not typical of anything. If we want to discover the essence of Carroll’s style we must put these great works to one side and look as what is left. And what is left, however, is still a very remarkable and consistently impressive body of work. Whether we would have heard of Carroll or not, had he not written the Alice books is another question, but to really understand the man we need to delve into some of the lesser known pieces like this one – and appreciate their merits – and see how consistent he actually was.

He was meticulous in the writing and publication of all his books - they had a physical beauty and high quality of production. His choice of illustrators was careful, significant and always appropriate. His works were educational yet rarely over-bearing and could be enjoyed by children without causing concern to the parents, (and enjoyed by their parents) They were always experimental and pushing the boundaries, yet carefully written and they reveal his remarkable and traditional education. And above all they were (usually) very funny and full of remarkably original well defined characters. Even in the logic books! All these characteristics will be found in a Tangled Tale.

Apart from the Alice books, where we all share an interest, our Carrollian tastes differ quite widely. Not everyone likes Sylvie and Bruno and quite a lot do not play the game of logic. Some probably dislike his serious poems and others don’t really laugh very much at the humorous ones. Well that’s the price Carroll pays for being so experimental and wide ranging in his work.

But in all those other works, I am sure we can find a consensus on what we think makes Carroll’s writing so remarkable and so enjoyable and if that is what we mean by - Quintessentially Carrollian - then A Tangled Tale fits this definition perfectly.